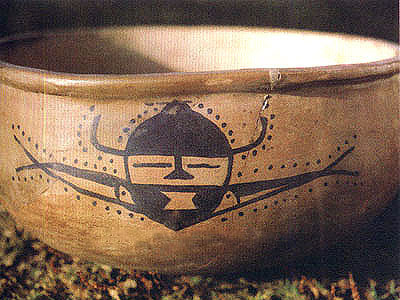

When we were traveling in China several years ago my dad often sent emails that started out like this: “since you’re in the area, why not go to…” When the next stop on our itinerary was Xian and the Terracotta Warriors, he made a huge deal for us to “not miss” the Banpo Neolithic Village, which showcased a matriarchal society dating back to 5000 B.C. (They call it a matriarchal society because “Women, the crucial labor force, were responsible for making pottery, spinning, and raising the family, while men fished.”) Although we were exhausted from seeing the Warriors, and disturbed at the parents who let their children (wearing the butt-less pants) pee on the dirt, and concerned for all the people who bonked their heads against the protective glass, we went. Turns out Banpo was incredible, and more amazing (shoot me now) than some Emperor’s maniacal dream to entomb an entire army of soldiers. The pottery had an eerie resemblance to Pre-Columbian pots,

the shape of this water jug “proved they understood physics”*

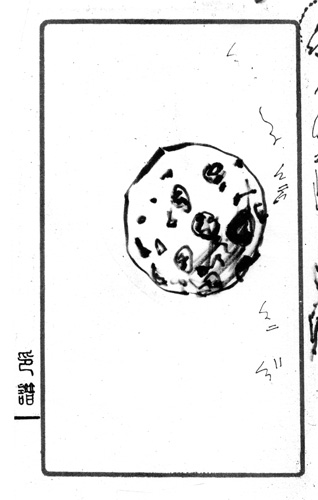

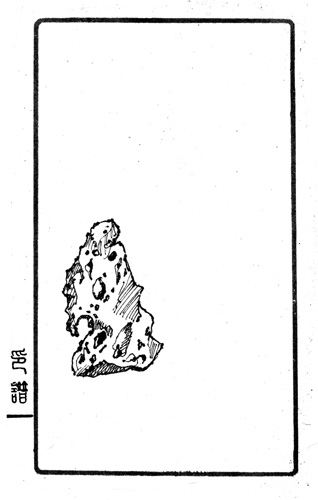

and best of all, they had a display of a “neolithic ball,” which was really just a rock, only they dated it to the neolithic period, just like the pottery, only it was just a rock.

When I told my dad that Banpo was better than the Warriors he wanted to know what I was smoking. I told him about the rock, and about musing over what the difference was between a really old ball-shaped rock and a slightly less old rock-shaped ball. His response was somewhere between the response he gave me when I told him I was going to art school, and when I told him you could see the Great Wall of China from the moon. If I could have seen his face I imagine it was closer to the art school moment.

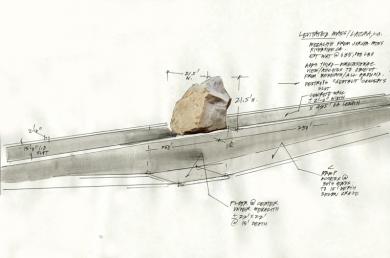

Turns out, that kind of thinking was excellent practice for contemplating the rock that is currently on its way from Riverside County to LACMA to become Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass.”

They date Heizer’s idea of the piece to 1968, but it took him all this time to find the right rock and then move it. Not like the rock is in any kind of hurry. It’s the ideal (if not the heaviest) piece of found art, actually, where it’s been lying dormant for 20,000 years and now it’s art. Well, it’s not quite art yet, it’s en route to becoming art. Which makes the whole transport and the gawking and the engineering so fascinating. (And oddly worth all the hoopla.)

Like Duchamp’s urinal, which is art because it’s not being used for what it was intended for, the rock is actually art only when it’s exhibiting a non rock-like state, in other words, when it’s moving. Heizer’s own expectation for the finished piece is that when the viewer walks under the rock, the rock will appear to be levitating.

Some funny facts LACMA keeps pushing over and over:

– “At 340 tons, the boulder is one of the largest megaliths moved since ancient times.” and “The transporter is roughly 260 feet long and 32 feet wide. The large size of the transporter enables the weight of the rock to be distributed over 196 wheels, in such a way as to prevent road damage… LACMA has worked with numerous city, county, and state agencies in acquiring proper permits and establishing the most prudent route for this endeavor.”

They make it seem that in the olden days when megaliths of this size were moved frequently (and usually before supper time) the ancient people were not bogged down by permits and worries of road damage, thus they were able to do similar feats of rockery with less dependance on engineering.

– Read my lips: “no public funds or taxpayer’s money was used to fund this project.”

One dumb fact I keep pushing over and over. The grassy lawn slated to become Levitated Mass used to be a nice place to run the dogs. Just saying.

*why this water jug is genius: when you put it in water, it tilts and lets water in. As it fills up, it will straighten itself automatically. If you get tired as you carry it, you just jab the sharp end into the ground and take a break.